The first solo Jet Ski ride around Australia has passed a major milestone.

After two stalled starts – interrupted by coronavirus lockdowns – Adelaide auctioneer Lindsay Warner, 63, has passed the half way mark on his journey around mainland Australia as of early July 2021.

Although the coastal edge of the continent equates to 35,800km (22,000 miles) following every nook and cranny, Lindsay Warner’s journey will likely add up to in excess of 15,000km (9300 miles) – one of the longest Jet Ski adventures in the world – as his route is mostly offshore, covering the shortest distance possible from point to point.

The total distance will be tallied once the lap is complete, but by any measure it is an epic feat – which has largely been self-funded, and relied on support from volunteer communities as well as family and friends.

In addition to conquering a seemingly impossible goal – a solo lap of Australia on a Jet Ski – Lindsay Warner’s other motivation has been to raise awareness for male mental health.

His 2017 Kawasaki Ultra Jet Ski – which he bought secondhand – was specially-prepared for the record ride.

In addition to the Kawasaki’s standard 78-litre fuel tank, there is a 60-litre bladder on the rear deck, four 20-litre jerry cans in the footwells, plus four 20-litre jerry cans on a sled towed behind the craft.

In total, there is 298 litres of fuel capacity but Lindsay Warner has only planned to carry a full load on four legs of the journey.

Most days, the jerry cans on the sled are empty, saving weight and minimising wear and tear on the whole set-up.

So far, his Jet Ski – and all the gear attached to it – has barely skipped a beat.

The intake grate picked up a lump of wood early in the journey in South Australian waters – requiring a tow from a fishing boat after Lindsay Warner set off a distress flare for the first time in his life (and for the first time in the journey thus far).

And the driveshaft bearings had to be replaced in the past week, near Townsville, after he noticed a grinding noise.

Most nights along his epic adventure, Lindsay has camped on the beach, or stayed in Coast Guard boat sheds, backpacker accomodation, or caravan parks.

On rare occasions he has been able to stay on fancy boats – owned by friends of friends – docked at marinas.

But from here on, Lindsay Warner says he plans to stay in proper accomodation every night as he enters crocodile country.

“I’ve been doing this trip as frugally as possible, but I’m now heading to parts of the Australian coastline where it’s not possible to camp on the beach, there are too many crocodiles,” Lindsay Warner told Watercraft Zone in a recent phone interview.

It’s been quite the effort just to make it this far.

Lindsay Warner started his epic around Australia journey in Exmouth, half way up the coast of West Australia and just south of Broome, on 1 March 2020.

However the journey had to be paused at the end of March 2020 due to border closures amid Australia’s strict coronavirus travel restrictions.

He had travelled all the way down the West Australia coastline past Perth, around the southern most tip of West Australia, and made it as far as Esperance – the remote town between Albany and the South Australian border.

As travel restrictions began to ease across Australia, Lindsay Warner returned to Esperance a year later, on 1 April 2021, to continue his epic journey.

He followed the vast and remote southern coastline across the Great Australian Bight – much of which is bordered by cliffs at the edge of the desert – crossing from West Australia into South Australia and, eventually, into freezing Victorian waters.

Travelling in the cooler months of April and May – the lead-up to the southern hemisphere winter in the coolest part of Australia – Lindsay Warner had made it across most of the Victorian coastline, passing Geelong, Melbourne and the Mornington Peninsula.

However, he was forced to abort his mission for a second time – just shy of the border between Victoria and NSW in the remote town of Mallacoota – due to another round of COVID travel restrictions and border closures.

Although Lindsay Warner was travelling by water, he was still compelled to abide by border lockdown restrictions – or risk being fined and forced into quarantine.

And so his solo Jet Ski ride around Australia was paused again, on 21 May 2021, until travel restrictions eventually eased.

After about three weeks off the water – nine days in Melbourne and 14 days near his hometown of Adelaide – Lindsay Warner commenced his lap of Australia for the third time on 26 June 2021, and hasn’t stopped since.

In just three weeks, Lindsay Warner has ridden his Jet Ski along almost the entire east coast of Australia – from Mallacoota in Victoria, to Cairns in far north Queensland. A remarkable effort by any measure.

With three-fifths of his journey completed, Watercraft Zone caught up with Lindsay Warner in Cairns on 18 July 2021 while he was in the middle of a two-day break to get his 2017 Kawasaki Ultra Jet Ski serviced.

Lindsay Warner hopes to round the northern most tip of mainland Australia within a week from today, before tracing the Cape York coastline past Seisia and Weipa, and then heading around the Gulf of Carpentaria and stopping in Darwin in about three weeks.

From Darwin, Lindsay Warner estimates it will take about two weeks on the water to arrive in Exmouth, where his journey began.

Lindsay Warner has, on average, been riding five days out of seven and his pace is usually around 30 to 35km/h (18 to 22mph), depending on conditions.

When possible he hits the water at first light while the ocean is generally calm and the winds are low, aiming to cover between 150 to 300km (93 to 186 miles) most days.

Perhaps as incredible as the journey itself – and the physical and mental toll – is the fact that Lindsay Warner has largely funded this effort out of his own pocket.

“It’s just through my own money,” Warner told Watercraft Zone. “A few people have given me some donations or donated their time when working on the ski.

“I’ve had a couple of people buy me tanks of fuel, which has been good, but that’s a rarity. I’m very thankful when they do it,” said Warner.

“I had budgeted on spending about $15,000 on fuel but the final bill will probably come in closer to $20,000. Once you add up everything else such as accommodation and food, it’s probably a $40,000 exercise at a minimum.”

According to his spreadsheet, the whole trip should take 101 days on the water, not including rest days.

“That’s three and a bit months, so if you have days off, it will quickly blow out to a five- or six-month journey,” says Warner, who has planned every last detail as best he can.

“I know where I’m going to be every day,” he says. “I call ahead and speak to the Coast Guard, I’m in close contact with emergency services so they know I am out there if I have to set off a safety beacon.”

Lindsay Warner was going to make a quick two-day return trip across to Papua New Guinea from the northern tip of Australia, however current coronavirus restrictions axed those plans.

Plus he can use the time to get back on schedule after maintenance stops in Townsville and Cairns.

Lindsay Warner bought the 2017 Kawasaki Ultra Jet Ski secondhand from one of the trio who crossed Bass Strait from Victoria to Tasmania – and back – in May 2017.

This Jet Ski is one of three identical non-supercharged Ultra models prepared by motor racing driver and team owner Todd Kelly, so Lindsay Warner was able to take advantage of the modifications to the craft.

“The Kawasaki Ultra is the strongest hull out there and the best suited to this type of journey,” he says.

“It’s a very solid hull. Unbreakable almost, I would suggest. It’s made out of fibreglass, so it can be repaired if needed. The other brands have lightweight hulls that aren’t suited to this sort of riding.”

The fuel bladder on the rear deck and the jerry cans on the sled are plumbed into the main tank, so there’s no need to mess around with a jiggle hose or a funnel.

A solar panel helps power the fuel pump from the auxiliary tanks.

One of the four legs that will require a full load of fuel is the Kimberley region in the far north of West Australia, between Darwin and Broome.

There he estimates he will need at least 420km of fuel range and has allowed 11 hours to knock off that stretch of coastline in one go. He plans to hit the water at sunrise.

As for personal maintenance, Lindsay Warner says he has a modest breakfast, skips lunch, and tries to get a decent feed each night, preferably with extra carbohydrates.

On the water, he might snack on a chocolate bar or a protein bar. There are two to four litres of drinking water on the craft.

“I’ve lost so much weight on this trip, it’s like doing a gym session for between four and eight hours a day,” he says.

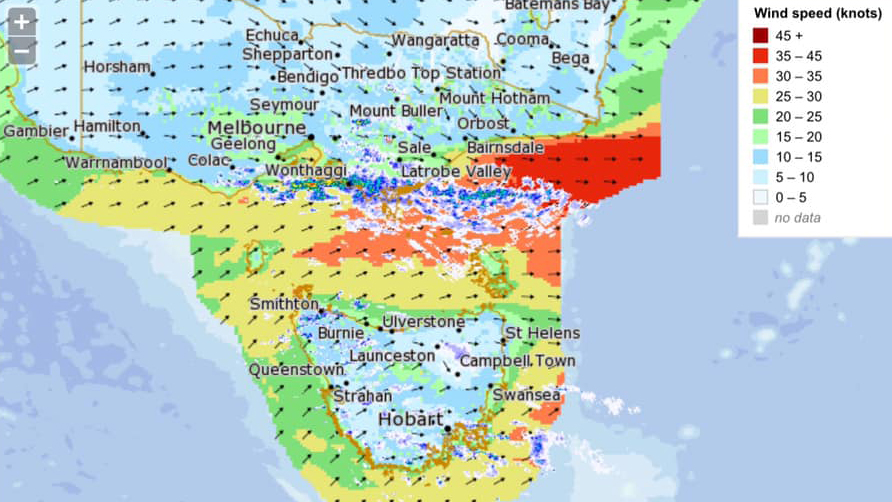

Lindsay Warner says he prefers to stand during most of his time on the water, as it’s easier on the body. And he tries to ride in good weather, but doesn’t always have the luxury of time.

“The ocean swell has got to be bigger than three metres before I will think about not heading out, or calling it a day earlier than planned,” he says. “Wind is your biggest enemy, because that creates steeper waves.”

Some days are better than others, however.

“I’ve ridden in two to three metre swells that have been like glass because there was no wind,” says Lindsay Warner.

“Some days a whale will pop up beside you, within 50 metres,” he says. “It can give you a bit of a fright but it’s whale migration season, so the east coast of Australia is like a highway for them at the moment.”

Lindsay Warner says he doesn’t hug the coastline, and at times is 5km off the shore as he navigates a straight line from point to point.

“The furthest I’ve been offshore is 35 kilometres, between Bunbury and Margaret River (in West Australia),” he says. “It was a 75 kilometre crossing.”

The Kawasaki Ultra Jet Ski is fully kitted out for the journey.

Lindsay Warner has a Lowrance navigation unit on the craft and two portable Garmin devices as a back up.

He has four emergency transponders that can signal his location at the press of a button, a satellite phone, and a regular cell phone (though signal coverage is patchy).

One emergency beacon is connected to a covered switch near the instruments – and there is a personal locator beacon in the console, and another attached to his life vest.

A full size EPIRB is attached to a marine rescue module at the rear of the Jet Ski, designed to separate from the craft if it starts to sink.

The marine rescue module contains emergency food rations, water, flares, and flotation devices.

“If the Jet Ski starts to go under, I can grab the emergency box,” he says. “It comes off the ski if it tips upside down, and is able to float.”

There is also a VHF marine radio – connected to a large aerial – and the Jet Ski is fitted with technology that enables other ships and the Coast Guard to see his location.

Before he started the journey, Lindsay Warner practiced being towed, so he could determine the ideal towing speed and length of rope.

He says being towed at 11 to 12 knots with 15 to 20 metres of rope seemed to work best in his circumstances.

Spare parts on board are kept to a minimum: spark plugs and oil.

He has a paddle, scuba flippers, and goggles should the worst happen.

Lindsay Warner also has a top tip for anyone thinking about getting a USB charging port fitted to their Jet Ski.

“Don’t do it,” he says. “My Jet Ski has two USB ports but the salt just gets to them, even though they are tucked away in a console.”

Instead, he says, it’s better to use slim portable battery chargers and store them with the phone in a waterproof case.

“Then when you get to land each night, you can charge them and your phone and you’re good to go,” he says.

Lindsay Warner says he has received invaluable help from the Rotary Australia volunteer community, who have assisted at numerous stopovers with food, fuel, and accomodation.

“Some close family members have also helped considerably with logistics and finances,” he says.

“This journey is also about men’s health awareness. I have had many conversations with many men (and women) about ensuring men have medical checkups, and that they find a friend to talk to during times of need.”

Once the trip is complete, will this be an official record? That’s yet to be determined, but the signs are positive.

A group of four Jet Ski riders lapped Australia in 2012 but were accompanied by a boat and road crew, and may have skipped some remote legs due to the logistics of getting fuel to the craft.

To prove he has covered every inch of Australian coastline, Lindsay Warner has kept a diary, taken photos – and he shares every step of his journey on smartphone apps such as Relive and Spot-X.

Lindsay Warner believes this could be the first solo lap of Australia on a Jet Ski.

The challenge for record-keepers is that Lindsay Warner’s journey was interrupted by border closures during the pandemic.

He is hopeful, however, of setting a record for the longest open ocean solo journey by Jet Ski, even if the complete lap of Australia was not continuous.

One Guinness World Record for a journey by Jet Ski, personal watercraft, or “aqua bike” in open and closed waters is listed at 17,266km set in 2006 over 95 days, from the west coast of North America to Panama.

A Guinness World Record for a journey by Jet Ski, personal watercraft, or “aqua bike” in the open ocean is listed at 7404km set in 2018 over 31 days, from Norway to Spain.

Whether Guinness World Records recognises Lindsay Warner’s efforts or not, it will likely be some time before anyone repeats his epic feat.

His circumnavigation of mainland Australia will stand alongside his previous trip two years ago, circumnavigating Tasmania.

In about a month from now, if all goes to plan, Lindsay Warner will have completed the set.

MORE: Everything Kawasaki

MORE: All our news coverage in one click

MORE: Follow us on Facebook so you don’t miss any future updates

Photo credit: All images courtesy of Lindsay Warner and are used here with permission.