Want to buy a Jet Ski or personal watercraft, but don’t want to start with a new one?

You can save thousands if you’re prepared to buy a used watercraft, but it pays to be patient and do a long list of checks.

There is plenty of choice in the used market among the BRP Sea-Doo, Yamaha WaveRunner, and Kawasaki JetSki ranges, but all of them require a thorough once-over before you buy.

Here are our Top 11 Tips for those new to the sport, looking to get a Jet Ski or personal watercraft that won’t break the bank.

1. Check the year model and ID, do a finance check

The model year for most personal watercraft is hidden in the vessel’s identifying number.

Cars have VINs, vessels have HINs. On jet skis the relevant serial numbers are usually on a black strip of plastic riveted to the rear deck.

To check the year model against the seller’s claim, for example, this year’s watercraft ID numbers end in 20 (for 2020) and last year’s ended in 19 (2019), and so on.

Unlike cars, which have an exact build date, the watercraft industry works on model years.

Sea-Doo, Yamaha and Kawasaki tend to changeover their models in the last few months of each calendar year. For example, some watercraft tagged as 2020 year models had already arrived in Australian showrooms in late 2019.

The industry does this because of the time it takes to build up supply of next year’s models.

Also check the vessel’s age on the registration papers and/or the date on the receipt when the craft was purchased new (if the seller still has a copy). Check if it has the balance of the factory warranty (three years for Yamaha and Kawasaki and two years for most Sea-Doos and three years on some Sea-Doos during special promotions).

It’s worth noting it is possible a 2018 model-year watercraft may not have been sold until 2019 (some craft sit in dealer stock for a while), so the date of first registration and/or the date on the receipt when the craft was bought new should give you a complete picture of when the jet ski hit the water for the first time and when the warranty started.

Once you’ve correctly identified the jet ski, be sure to check if it has any outstanding finance owing. Just like cars, watercraft sold in Australia are listed on the Registered of Encumbered Vehicles (REVS). There have been some instances recently of customers unwittingly buying jet skis that still have finance owing on them.

2. Check the hours

Rather than an odometer that measures the total kilometres a car has traveled, jet skis clock up hours.

Some jet skis might have only been used for 10 or 20 hours a year (this would indicate light use); if you see any with 100 hours or more over, say, two or three years old, they clearly have an enthusiastic owner.

There is no industry average on annual jet ski use, but we have seen some that are four or five years old with more than 200 hours on them and still running fine – because the owners have maintained them properly, and replaced parts as they need replacing.

A two- or three-year-old jet ski with 10 to 20 hours might seem appealing, but if it has not been used for an extended period, not serviced regularly, or not flushed properly, you could be in for a headache with seals that may have perished and engine oil that may have congealed.

A jet ski’s hours are an important consideration but they alone should not be a deciding factor. A well maintained ski with a lot of hours might still be worth considering. Which brings us neatly to the next point.

3. Service history

Most jet ski brands recommend routine servicing every 12 months or 50 hours, whichever comes first. Some owners follow a six-month/50-hour service schedule (usually the beginning and end of summer as a guide) to make sure their watercraft is in top shape before the season starts – and checked properly before they pack it away for winter.

All new jet skis are sold with service log books, so you can check how regularly the watercraft has been maintained. If you think something looks fishy (the service stamps look fresh and the details appear to have been filled out on the same day, but with different dates), don’t be afraid to ring the dealer or service agent and compare the service history with their database.

Even if the service log books look legit, it’s often not a bad idea to contact the dealer about that craft in any case. Keep in mind, though, they will likely want to look after their existing customer (so they can sell them a new one), or they may try to convince you to buy a new one from them.

In our experience, most jet ski dealers are generally honest because the industry is so small. If you’re new to the sport they will want you to keep bringing the ski to them, so there’s an incentive for them to tell you the truth about the craft you’re looking to buy.

Servicing costs vary from brand to brand (most Sea-Doo models, for example, need to have panels removed to access the engine, which adds to labour costs) but generally a basic service (oil and filter) should be in the $350 to $450 price range and major services (spark plugs and other maintenance items) can be $550 to $750. Every dealer is different so be sure to get a quote first.

4. Check the hull

You see jet skis ridden up onto the beach, especially on surf rescue TV shows. What the cameras don’t show you is that those watercraft have been fitted with a special layer to protect the hull from the abrasive sand.

Our tip: wherever possible, don’t beach your ski. There are plenty of lightweight plastic anchors (with about a metre of chain to help it grip in choppy conditions or when there is a strong current) and sand bag anchors (for calmer waters) that will do the job and keep your craft off the sand.

The problem is, this lesson is usually learned the hard way. Speaking from personal experience, the paint on most jet ski hulls wears and marks easily; some hulls are prone to exposing fibreglass if they’ve not been treated properly. This should be a warning sign to walk away as repairs can be costly.

As uncomfortable as it is, you really need to get underneath the craft. Lie on your back, and run your hand all the way along the spine of the hull. Try to avoid doing this at night or in the rain. You need plenty of light and a clean surface to make sure there’s no major hull damage.

Scuff marks are normal, but run your finger over them to see if it’s a surface scratch or if it has dug through to the fibreglass.

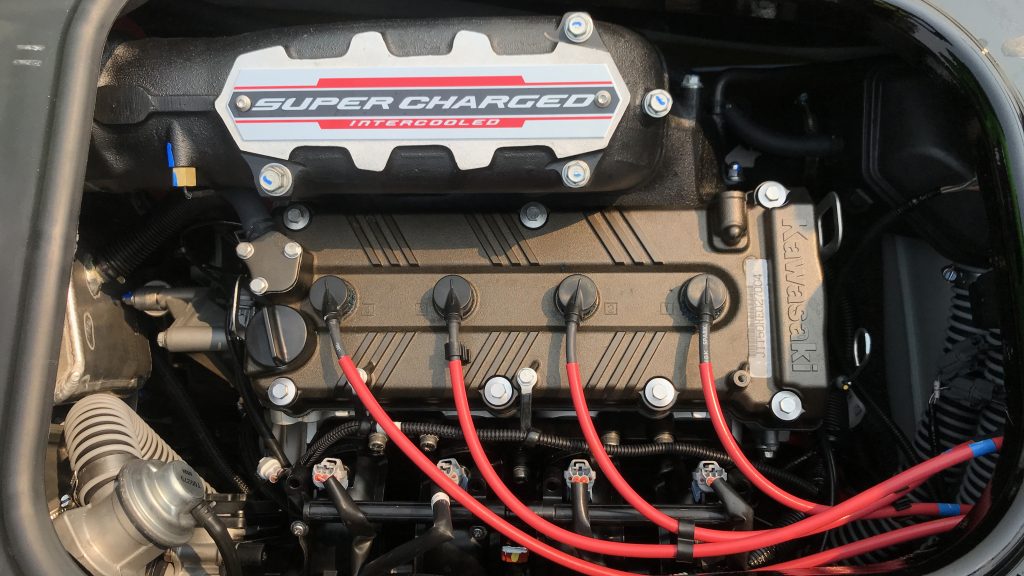

5. Check the engine

This is the hardest and most time consuming task. If the rest of the jet ski looks up to scratch, so to speak, and you’re about to lay out some money, you need to do a compression test on the engine.

Sea-Doo engine bays are notoriously hard to get to so you may need some expert help, or the help of a dealer who may need to remove panels. Yamaha and Kawasaki watercraft have more accessible engine bays.

You’ll need the seller’s permission to do a compression test, of course, and you’ll need to bring a mechanic and testing equipment with you.

This test can flatten the battery so some sellers may not be keen, however, if they have a trickle charger, the battery will be back to normal in no time.

If you’re not mechanically minded and don’t know someone who knows what to do, ask the seller if they will meet you at the workshop they take the jet ski to for routine maintenance – or find an independent mechanic (preferably with marine experience) to do this check.

If the seller is keen to get rid of the craft, they may be happy to meet you at their local jet ski dealer or an independent mechanic after you’ve at least taken the time to see the ski at their place first.

You may have to pay someone for this check if you’re not doing it yourself. Be sure to negotiate a price at a workshop beforehand if it’s not going to be done free-of-charge. A little bit of money at this point could save you thousands in engine repairs or rebuilds.

6. Look for water inside the hull

It is normal for Jet Skis and personal watercraft to have a small puddle of water in the bottom of the hull, no matter how watertight they are. By a little bit, we mean about a cup or two.

More water than this means either the hull has not been drained properly after a clean (it’s recommended to lightly spray fresh water in the engine bay after a ride in salt water), it has a leak, or someone left the “bungs” (drain plugs) out and hasn’t been able to get rid of the evidence.

Without drinking a gallon of it, try to taste test the water to see if it’s fresh or salty. Be sure to make it only a quick dab taste, there could be oily residue in the mix.

7. Check the oil and oil filter

The base of oil filters can corrode if the jet ski has been used in salt water a lot and hasn’t been cleaned properly afterwards. A good routine maintenance tip is a light spray of an approved water repellent (Yamaha has Yamalube, for example, which has been tested on that brand’s rubbers and plastics etc).

There are some other heavy duty water repellent sprays available but make sure they don’t do more harm that good.

The condition of the oil filter (and the oil on the dipstick) will be a good indicator of how recently the watercraft was serviced, and the fussiness of the owner.

8. Check it has the right security key/lanyard

All three personal watercraft brands have different ways of locking and unlocking their immobilisers.

Sea-Doo and Kawasaki have security tabs on the end of lanyards – that clip onto on knob or slot into the ignition – while certain Yamaha WaveRunners come with two remote key fobs, similar to those used by cars.

Certain Yamaha WaveRunners made from 2019 onwards require a four-digit PIN code to be tapped into the digital dash, avoiding the need for a security remote. If you buy one of these, make sure the owner tells you the code.

If you’re buying an older Yamaha equipped with an immobiliser, make sure you get both remote key fobs; replacing one of these is expensive and requires a series of checks to make sure you’re the rightful owner.

While you’re at it, make sure you get the log books and the owner’s manual.

9. Check the condition of the top deck and seats

It is normal for older jet skis to have the odd mark here and there. What you are looking for are repairs that have been covered up, so bring a mate with paint experience to spot any mismatched colour on the bodywork and hull. Avoid inspecting the craft at night or in the rain for this check.

Check the rub strips along the gunwales and the plastic bumpers on each corner. It’s normal to have some damage, but worth noting so you have the complete picture.

On Jet Skis and personal watercraft equipped with side mirrors, check they’re still fitted properly (it’s common for them to snap off if bumped or tugged the wrong way).

It’s also worth having a close look at the seats for any rips or loose stitching. Check if the seat is original material or done by an aftermarket trimmer. Some aftermarket trimmers are excellent, others not-so-much.

10. Get a workshop inspection, take it for a water test

You’ve come this far and you’re about to buy. You wouldn’t buy a car without taking it for a test drive or getting a mechanical check. And you wouldn’t buy a house without a building inspection.

Taking a jet ski on a water test is definitely a hassle for the seller and would likely only happen after you’d given the craft a decent once-over – and if you were genuinely serious about buying.

So our advice is ask a nearby Jet Ski or watercraft dealer or mechanic if they will do an inspection of the secondhand craft you plan to buy.

Some dealers we spoke to said they would happily do a compression test (some even offered to do it free of charge as a goodwill gesture if they thought the buyer would bring the craft back to service there), but we got mixed reactions when we asked about a more thorough pre-purchase inspection.

One dealer said he would charge $110 and do his best to find faults, but always warned customers they can’t see inside the engine and they’re not liable if something goes wrong the next day.

Another dealer said he would look at it but only to rule out a craft, rather than say “buy this one” in case he was liable for a subsequent unforeseen failure.

“You can do your best to look for obvious signs of abuse or lack of maintenance, and a compression test goes part of the way to checking the health of the engine, but the reality is you can never be 100 per cent sure there isn’t a problem you can’t see,” said one of Australia’s largest watercraft dealers, who asked to remain anonymous.

“Taking it out on the water for a test is a pain, but if the seller is keen to sell, and you’re a fair dinkum buyer, they will at least think about it. But I would get a dealer to inspect it first, then see if the seller will let the buyer ride it even if it’s just for five minutes,” he added.

11. Check the trailer

A lot of buyers get excited about the watercraft, but it’s worth running a good eye over the trailer. Look for signs of corrosion on the frame, check the skids or rollers line up properly with the hull (make sure they’re not rubbing on the chines on the hull).

Check the tail-lights work and the winch, winch strap, and jockey wheel are in good order.

Most jet ski trailers tend not to last beyond 8 to 10 years, so find out when it was first registered.

Check the condition of the tyres. It’s hard to check the condition of the bearings, but it would be worth budgeting for new tyres and new bearings as soon as you take delivery.

Make sure the watercraft and trailer are insured before you tow them away, otherwise if anything goes wrong on the drive home you could be out of pocket big time.

MORE: All our Sea-Doo coverage in one click

MORE: 2021 Sea-Doo prices

MORE: All our Yamaha coverage in one click

MORE: 2021 Yamaha WaveRunner prices

MORE: All our Kawasaki coverage in one click

MORE: 2021 Kawasaki Jet Ski prices